Early European Contact Years

Prior to 1637, an Algonquian native nation variously identified as Matouwac, Metoac (Dutch) or Montaukett (English) – inhabited all of Long Island east of the present-day Queens County line, which marked the furthest eastern extent of Delaware/Lenni Lenape territory. This territorial delineation was emphasized by the language difference between western and eastern Long Island natives. The Lenni Lenape tribes (Canarsee, Rechaweygh) spoke the Algonquian R-dialect of the Munsee, while the Montaukett spoke an Algonquian Y-dialect similar to the Pequot, Mohegan, Niantic, and Narragansett Nations of eastern New England. The historic record regarding the Montaukett is not so clear and positive, but there is sufficient data available to indicate that at the time of European discovery, their closest connection was with the Mahican Nation.

The Montaukett Algonquian nation, with an estimated population of over 10,000, had little direct contact with the English and Dutch settlers who resided respectively on the southern New England mainland, the western end of Long Island, and on Manhattan Island. For the most part, during this time Montaukett contact with the outside world was mediated through their kinsmen, military allies and enterprise partners, the Pequot Nation.

The Montaukett were major manufacturers of Wampum – the traditional, sacred shell beads made from shells found primarily on Long Island. Wampum was widely used as a standard unit of exchange among Northeast woodlands tribes. Hence, Long Island could be considered the “Fort Knox” of pre-colonial Northeast America. The relationship between the Pequot and the Montaukett can be characterized as Long Island-based Wampum manufacturers and mainland-based Wampum distributors. The English assertion that the Pequot were a “savage, violent” tribe that forced the Montaukett into subjugation is unproven. More likely this was colonial propaganda used in part to justify their annihilation of the Pequot.

When Europeans came to the Americas they realized the importance of Wampum to Native people and quickly adopted it as their medium of exchange. This lead to inevitable conflict between the Pequot and the European settlers who were determined to gain control of the Wampum distribution. Thus began a colonial propaganda campaign to demonize the Pequot as “fierce, cruel, and warlike” because they refused to concede economic control to the Europeans. This effort culminated in a short but destructive military engagement where militiamen commanded by Lion Gardiner attacked and destroyed the Pequot stronghold at Mystic, Connecticut. This became the first recorded incident of aboriginal genocide perpetrated by the intruders called “Puritans.” Whatever happened at Mystic, the balance of power in southern New England was forever changed and European domination of New England and Long Island became inevitable.

According to the writings of Lion Gardiner, three days after the Mystic battle, Wyandanch, a younger brother of the Long Island Grand Sachem Poggatacut, met with him in Connecticut to seek friendship between Long Island Natives and the English. These negotiations resulted in the original English occupation of the east-end of Long Island beginning with Gardiner’s seizure of the island called by the Montaukett Manchonacke (island where many died) – which he eventually renamed Gardiner’s Island. Gardiner’s version of events portrays a benign and friendly take-over of the seat of Montaukett territory. In retrospect, given the savagery he displayed against the Pequot, this placid version of history seems unlikely. However, it cannot be denied that Gardiner’s initial intrusion resulted in the incorporation of the entire Long Island sub-region, its peoples and its valuable natural resources, into the southern New England colonies.

When the first permanent English settlement on the East End was established in 1640, all of Long Island was claimed by the Dutch who actually only occupied the small Lenni Lenape territory on its western tip – and never successfully penetrated any of the Montaukett territory. The English settlers could not ignore opposing claims from the other colonial regional power and this influenced the manner in which they sought resolution. On occasion, opposition to English territorial acquisition was extinguished through direct force of arms. At other times the English accomplished their goals through overt coercion, such as falsified treaties and deeds supposedly negotiated between Montaukett, Dutch and English authorities.

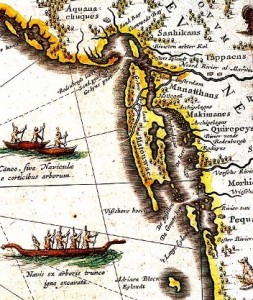

During the mid-17th century contact period, the Montaukett constructed a series of “fortified places” due to increasing interaction with the ever-encroaching traders and settlers. Archaeological records reveal the shape, size, siting, and use of these forts. Some were constructed more for trade, others more for defense. The fact is Long Island had more mid-17th century Native forts than any other area of the country. The Montaukett Fort discovered on Fort Hill in Montauk Point was one of the earliest and the best for its time. It is the only one of the two found so far, to be shown on a 1658 map of Long Island.

The most dramatic material evidence of the contact between the first inhabitants and the colonizing Europeans is the Pantigo burial site, dating from ca. 1650-1750, soon after the 1648 founding of East Hampton. The seventeenth century contact with explorers and traders had brought diseases, mainly smallpox, against which the American indigenous population had no immunity. This had decimated the indigenous population by about 90% throughout North and South America within a few generations.

A Montaukett grave site that was excavated in 1917 showed that deceased Montaukett were buried in the traditional flexed position without coffins (with some in the European extended position). Most of the 39 recorded graves contained a majority of European trade goods. Apparently, trade items had supplanted those of aboriginal manufacture. Although these archaeological finds provide evidence of European acculturation in the arena of material possessions; other evidence indicates the Montaukett retained traditional wigwam housing (1880s), much of the hunting and gathering lifestyle (1870s), the use of herbal medicines, and traditional gatherings into the twentieth century.

Colonial Era

As the initial contact period became the historic or colonial era, the Montaukett and other Native people were drawn into the transplanted European economic sphere in order to buy the new ‘necessities,’ such as gunpowder, flour, sugar, clothing, Dominy furniture, etc. The colonial economy created an insatiable need of manual laborers for whaling, farming, herding, dairying, cheese and butter production, textile production, and craftware. Hence, Montauketts became a convenient pool for servants and slaves. Of 90 Suffolk County wills probated from 1670 to 1688, 24 listed English, Negro, and Indian servants and slaves. Their value was second only to cattle owned. Of this 24,or 8% were listed as “Indian captive servant” or “Indian slave girl.” It should be noted that many enslaved Natives were transplanted from the Carolinas and the Caribbean and absorbed into the Montaukett population.

Another application of colonial servitude was forcing Montaukett to produce huge quantities of Wampum to pay fines levied upon them for infractions of local laws (which they often did not understand). The Wampum was then used by European traders to purchase furs from the northern territories. Since the largest amount of whelk shell for making Wampum was found on eastern Long Island beaches, that area became the “mint” of New Netherland. Further participation by the Montaukett in the new economy was service as militiamen in all the provincial campaigns before the French and Indian Wars and in the American revolution. They served out of proportion to their numbers in the population and left many Montaukett settlements with a large number of widows. This led to intermarriage with Anglos, African-Americans, and other ethnic groups.

Most Montaukett worked for the East Hamptoners and helped make colonial life as comfortable as it was. They were gin (fence) keepers of the livestock pastured at Montauk and laborers for the Gardiners and others. The men used traditional woodworking skills to make piggins, ladles, and bowls for settler homes. They provided fish, oysters, and game for them. Stephen Pharaoh’s pay is recorded for “bottoming” (rushing) Dominy chairs. As skilled shore whalers, Montaukett men were fought over by entrepreneurial East Hamptoners to be their crewmen. Many of today’s labor laws find their origin in the rules enacted by the seventeenth century Town officials to control the cutthroat whaling labor practices of that day.

Montaukett women used the spinning wheel to spin yarn, a necessity for all knitwear and weaving of essential cloth. They became expert makers of butter and cheese, which were major cash ‘crops’ for their masters. Baskets, scrubs, jellies, and fine hand work provided cash for themselves. They cared for the mothers and children of colonial families, and were encouraged by the society to be the sex objects of the men; hence the Montaukett descendants of some of the early settlers.

Besides Montaukett participation in the economic sphere, their souls were sought by the English and Scottish missionary societies to create more tractable workers. The first missionary in the 1740s was Azariah Horton of Southold, a graduate of Yale, who was not very successful. He recommended a successor, Samson Occom, a Mohegan who came first as a teacher, then was ordained in the Presbyterian Church after tutelage by the Rev. Samuel Buell.

Occom was one of about 27 Native men educated in the European manner by Rev. Eleazer Wheelock and fellow clerics. He was one of the few to survive and the only one to have his portrait painted by the noted colonial limner Nathaniel Smibert. He also was pictured by other paintings, mezzotints, and lithographs; thus we know how this man appeared. Occum is credited as the inventor of sensory teaching methods a hundred years before Maria Montessori. He was a composer of hymns still sung in the Presbyterian church, a skilled craftsman and bookbinder, an expert gamesman to feed his family, etc. He was the only Native clergyman to keep a diary, which became an alternative source revealing unknown information pertaining to that early historic period.

Occum came to believe that the Montaukett could not survive as a unique culture in the climate of genocide fostered by the Easthampton government. Samson Occom and his brother-in-law David Fowler, along with contingents of the Mohegan, Pequot, and Narragansett, led an exodus of Long Island and New England natives to the Oneida Territory of up-state New York, where they established the Christian town of Brothertown. The first settlement was aborted in 1776 by Revolutionary War hostilities, but was re-established after the war in 1784.

Occom was the minister of the settlement and died there in 1792. His grave is unmarked but is thought to be in or near this Brotherton cemetery on Oriskany creek behind the house of his brother-in-law David Fowler. Mary Fowler Occom’s brothers Jacob and David were also educated by Wheelock and played important roles as translators at the Treaty of Fort Pitt and other colonial parleys. It was David, teaching at Oneida, whose tales of the abuse of the Montaukett moved an Oneida chief to grant them land.

Instead of a haven forever, within a generation the Brotherton lands were being trespassed upon by settlers from New England. A N.Y. State Assembly commission awarded one third of their land to the trespassers. The Brotherton were forced to move westward, finally to a spot in Wisconsin they named Brothertown. They were an ‘Americanized’ group who were highly productive in boat-building, lumbering, milling, and farming. They were the first tribe to become U.S. citizens, and did so to avoid President Andrew Jackson’s drive to force all Indians west of the Mississippi. As a consequence of the partition of their reservation, they lost the land which had become their farms. However, the Brotherton continued their gatherings over the years and have recently filed for re-recognition as a tribe.

Modern Era

By the nineteenth century tuberculosis had taken the place of smallpox and other European diseases as the scourge of the Montaukett. Easthampton church death records, which may be incomplete for the Montaukett, indicate that 14 of 39 Native deaths between 1825 and 1879 were of consumption, with the deceased ranging from 11 months to 58 years.

As well as the usual farm and maritime work, nineteenth century economic activities of the Montaukett now included work in the developing factories of the area. They served as guides for wealthy hunters and the sportsmen’s clubs. Some delivered ice(see this photograph), provided livery service for the newly developing tourist industry, and produced wood and textile crafts still in early east end homes. The Easthampton Historical Society has a collection of this material culture – the baskets, mortars, pestles, piggins, ladles, bowls, and scrubs which underpinned 18th and 19th century life.

That period of Montaukett life and culture has been retrieved somewhat by the archaeological record of Indian Field, the last reservation home. It is now a county park called Theodore Roosevelt County Park – yet one more way to render invisible the original inhabitants. The artifacts excavated indicate habitation there from 1725 to about 1885. The excavation probably found the home of Charles Fowler (24 feet square of Anglo design with wood floors) and located other houses 30 feet square and 11 by 16 feet, as well as other structures 7 and 8 feet in diameter. The site’s “Indian barns” showed four variations of storage shelters and a well/cool-storage structure. Faunal remains indicate that they ate a lot of turtle.

Ceramic fragments found (4,539) indicate that more than half of their vessels were redware, the common ware of the early days. About 25% was pearlware, 17% white ironstone, 2% earthenware, and 1.25% porcelain. When this profile is calculated for other Long Island populations, it would tell us how the Montaukett compared economically and esthetically with other groups.

Maria Pharaoh’s “Diary,” the only such document about 19th century Native lifestyles, describes their self-sufficient, happy homesteading lifestyle – gathering, hunting, fishing, guiding sportsmen and selling crafts. After David Pharaoh died of TB, Maria and her children could not maintain the homesteading lifestyle. They were lured to move to Freetown, north of Easthampton village, by promises by Frank Benson that they could return in summer, would get a yearly annuity, and education for the children. The Benson family, who had bought Montauk peninsula from the Town Trustees, used it as a hunting preserve and planned to develop it. The promises were empty, the Montaukett homes at Indian Field containing their deeds and records were burned, and they were driven away from their ancestral home. Other Montaukett had moved away for better livelihoods to Eastville, a Native/African American settlement on the eastern side of Sag Harbor, while others scattered through the Island, living in enclaves in Southold, Greenport, Huntington and Amityville.

Through the newspaper accounts and censuses, it is apparent that most Montaukett women worked as domestics and servants, and most of the men worked at odd jobs, as laborers, and as farm hands, although some were skilled carpenters, whalers and seamen, masons, coachmen. However, when they had their pictures taken, they dressed in their best clothes, as everyone did.

By the twentieth century the Montaukett had disappeared from the Town Records, appearing only in legal records, in newspaper articles, in oral histories (such as Maria Pharaoh’s “Diary”) and the visual record shown in the Montauk volume. They attended school, were star athletes (John Henry Fowler was considered the Jim Thorpe of Long Island), rode bicycles, dressed as ‘dandies,’ held powwows or gatherings, and wore their regalia as a way of maintaining traditions. Among them was Olivia Ward Bush-Banks, a teacher, journalist, author, and poet whose collected works have been published by Oxford University Press. She was of Montaukett descent, attended powwows, and used her heritage in her work.

Judicial Genocide

The years leading up to the turn of the century was a period of disrespect, disappointment and devastation for Montaukett Indians. Montaukett leaders attempted to incorporate the tribe to establish legal standing. In 1871, this legislation was introduced in the state assembly. However it was successfully opposed by Easthamptoners who were eagerly waiting for the tribe to be declared extinct – which would erase the lien the Tribe still held on the land. The tribe endured another legal blow in 1871. The New York Supreme Court declared that the Montauketts were trespassing on the lands on Long Island supposed for many years to belong to the tribe.

Most Easthamptoners had an extremely low opinion of Montaukett. “…They are a lazy set with the single exception of Pharaoh, their King. They cultivate barely sufficient to keep them through the Winter, and generally beg the rest…” An 1874 editorial in the Brooklyn Eagle mused “…The poor savage is in the white man’s way, and must be out of it…” It went on to comment that, “…The Roman would have put those tribes to the sword ten years ago…” The Montaukett Royal Family became extremely vulnerable to an attack from extreme Easthamptoner factions. In 1875, Aurelia Pharaoh, mother of King David Pharaoh, was found dead on the floor of her cabin. Foul play was suspected. However an Easthampton jury declared that she died from “a visitation of Almighty God.”

The Pharaoh family was not out of harm”s way as late as 1885. The Brooklyn Eagle reported on September 5th, 1885 – “An Indian named Pharaoh, employed as mate on a vessel sailing from this port [Port Jefferson] is missing, under suspicious circumstances. His hat was found on the deck of a schooner, and he was known to have a large amount of money, foul play is suspected. He was the last of the Montauk Tribe.” The Norwich Courier reported that on Sept. 7, 1885, “The body of Pharaoh, son of King Pharaoh, the last of the once famous tribe of Montauk Indians, was found this morning in the bay with his face badly bruised as if done with a blunt instrument.” It was a common practice for newspapers at that time to include a “last of the Montauk Indians” reference in articles published about anyone with the Pharaoh family lineage.

In 1877, the seeds for challenging the tribe’s existence as a unique people were sown. A Brooklyn Eagle article declared, “There is a large admixture of African blood in the tribe as it now exists and only one or two families remain pure Indian.” The stage was being set for the final seizure of Indian Field. The same article went on to muse that – Of the Montauk Indians, only twelve remain, and whiskey will soon blot them from existence, and the name and memory of the tribe will be all that’s left of them. This was the hope of Easthamptoners in the years leading up to the final confiscation of Montaukett territory.

In 1878, the so-called proprietors of the land, the Easthampton Trustees of the Freeholders, filed a motion in the Supreme Court of Suffolk County for permission to partition the Montaukett reservation in any way they saw fit or to sell the entire parcel. Suffolk County Justice Dykman rendered a decision in favor of the Trustees, which the Tribe immediately vowed to appeal. However, early in the next year Judge Dykman confirmed the report of the referee in favor of selling the lands of Montauk in bulk. By October of 1879 the last vestige of Montaukett territory was sold to land developer Arthur Benson for the sum of $151,000. Almost immediately afterward, the Long Island Railroad revealed plans to extend their line from Patchogue to Montauk Point.

In 1897, King Wyandank Pharaoh applied to a judge in Riverhead for permission to bring action against the LIRR and the Benson estate to reclaim the Montaukett territory. The court ruled that neither Wyandank Pharaoh nor the Montauk Tribe of Indians had the right to maintain an action. “The plaintiff has not legal capacity to sue in that said plaintiff is not a natural person, nor an incorporated association permitted by law to maintain an action…nor is the plaintiff authorized by law to maintain an action as a tribe.” Wyandank Pharaoh immediately appealed this ruling to the State Supreme Court of New York.

Legal wrangling went on for twelve more years until October, 1910, where in a Riverhead courtroom attended by several Montaukett, State Supreme Court Judge Abel Blackmar issued his ruling that contained two key provisions. First, he validated the sale of the Montaukett reservation to Arthur Benson by the Easthampton Freeholders even though both the New York State and Federal constitutions circa 1777 specifically forbade the sale of Indian land. He did this by declaring – “…Const. 1777, { 37, forbidding the purchase of Indian land, did not terminate the right granted by the Dongan Charter [c.1686] to extinguish the Indian title, such Constitution providing that nothing therein should be construed to affect any grant of land within the state made by authority of the king, nor to annul any charter to bodies politic by him…” In other words, according to Judge Blackmar, land grants made under the name of an English King prior to the American Revolution superseded the constitutions of both the United States and New York State. Mysteriously, this sweeping ruling didn’t seem to apply to any land owned by whites.

Apparently Judge Blackmar decided that the Declaration of Independence, the Revolutionary War, the defeat of English colonialism and the U.S. Constitution’s ascendancy to the supreme law of this nation was not enough to override colonial law when it came to the seizure of Indian territory, although colonial claims to ownership of vast tracts of white-owned land became null and void.

The second part of his ruling was designed to eliminate any possibility of the Montauk Tribe of Indians seeking further redress beyond his court. Although he had absolutely no anthropological credentials, he ruled “…There is now no tribe of Montauk Indians. It has disintegrated and been absorbed into the mass of citizens. If I may use the expression, the tribe has been dying for many years…”

Blackmar’s declaration that the Tribe had ceased to exist extinguished the Tribe’s legal standing and consequently eliminated the possibility of further legal action in NY State courts. With Blackmar’s ruling, the judicial genocide of the Montaukett and the final seizure of the tribe’s last vestige of territory became New York State Law.

The current generation of Montaukett universally believe that this judgment was arbitrary, prejudiced, deficient and unconstitutional. Numbering in the thousands around the country and in the hundreds on Long Island, The Montaukett Nation is currently taking action to re-establish State and Federal acknowledgement and reserves their right to pursue the return of the tribal territory.