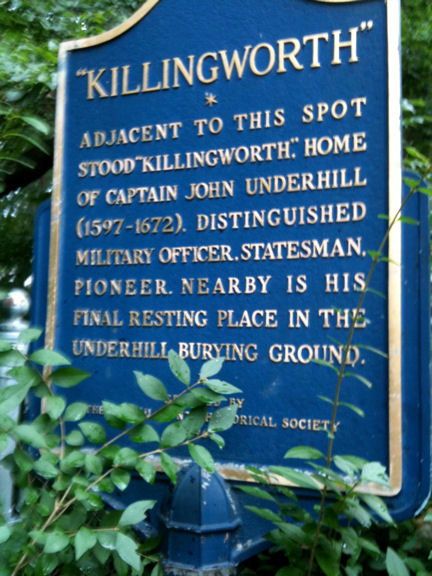

an article by Leighton “Blue Sky” Delgado

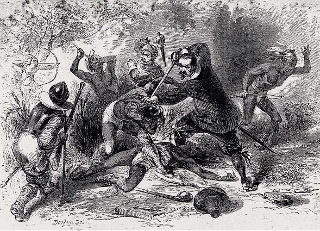

This was just the beginning of Underhill’s genocidal ambitions. Less than a year after Mystic, Underhill and his militia launched a surprise attack on a Munsee village in what is now Westchester County, New York wiping out the entire village, killing over five hundred Munsee Indians. For this, he was credited with ending what was later designated The First Munsee War. In two years of fighting, Underhill and his men had taken the lives of an estimated sixteen hundred Indians and destroyed most of the farmsteads on western Long Island.

In an effort to defend themselves against mass murderer Underhill, the Marsapeque Indians of Long Island built a fort called Fort Neck located in modern-day Massapequa. Underhill attacked and burned the Marsapeque fort, killing hundreds of Indians. The Marsapeque massacre stemmed from of a dispute between Tackapausha, Sachem or the Marsapeque and Dutch settlers who were trying to move the Marsapeque from their territory claiming that Tackapausha sold the territory to them. This was a classic example of mis-translation by interpreters who the colonials used to negotiate their so-called treaties with the Long Island Indians. When negotiating with Takapausha, the interpreter translated “purchase the land” to “share hunting grounds” which was the closest metaphor that could be expressed in the Algonquian language of the Long Island Indians. Takapausha asserted that he sold the Dutch the use of the land, but not the land itself.

This snippet of Long Island Indian history became the basis for the Amityville Horror House legend. This house located in the neighboring town of Amityville was supposedly possessed by vengeful Indian spirits who compelled a man to slaughter his entire family in the 1970’s.

In February 1644, still under Dutch contract, Underhill continued his Indian killing ways. He and his mercenaries slaughtered an estimated 500 to 700 Indians from the Siwanoy and Wechquaesgeek groups of the Wappinger Confederacy. The killings occurred at a winter village of the Indians located in present-day Pound Ridge, in Westchester County, New York. Underhill’s army also attacked Indian encampments north of Stamford, Connecticut, killing some 700 Indians in a single day. Underhill relentlessly fulfilled his bloody reputation as the “scourge of the Indians” and exercised his fundamental Puritan belief that “Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents.”

Dutch Navigator, Captain David Pieterszoon described Underhill’s slaughter in his journal:

“…Infants were torn from their mother’s breasts, and hacked to pieces in the presence of their parents, and pieces thrown into the fire and in the water, and other sucklings, being bound to small boards, were cut, stuck, and pierced, and miserably massacred in a manner to move a heart of stone. Some were thrown into the river, and when the fathers and mothers endeavored to save them, the soldiers would not let them come on land but made both parents and children drown…”

Using John Underhill and his mercenaries as their primary enforcer, English and Dutch colonials collaborated strategically to annihilate the Hackensack, Haverstraw, Munsee, Navasink, Raritan and Tappan bands from New Jersey; the Wecquaesgeek, Sintsink, Kitchawank, Nochpeem, Siwanoy, Tankiteke, and Wappinger from east of the Hudson; and the Canarsee, Manhattan, Rockaway, Matinecock, Massapequa (Marsapeque), Secatoag, and Merrick Indians on Long Island.

The population of the Long Island Indians in 1600 was estimated at 10,000. The effects of warfare and sickness reduced this indigenous population to less than 1000 by the year 1659. The Shinnecock, Montaukett, Unkechaug and eastern Matinecock tribes banded together under the Montauk or Matouwac confederacy and managed to avoid complete colonial extermination although most of these Indians were eventually condemned to indenture or outright slavery.

“…It may be demanded, Why should you be so furious (as some have said) should not Christians have more mercy and compassion? But I would refer you to David’s war, when a people is grown to such a height of blood, and sin against God and man, and all confederates in the action, there he hath no respect to persons, but harrows them, and saws them, and puts them to the sword, and the most terriblest death that may be: sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents; some time the case alters: but we will not dispute it now. We had sufficient light from the word of God for our proceedings…”

European conquerors like John Underhill routinely used the Bible to justify Indian extermination, and in many cases, the only escape from certain death was for Indians to reject their traditions and succumb to the European belief system. On Long Island and elsewhere, Indian names were banned, speaking the Algonquian tongue became illegal, the performance of native rituals could be punished by death from hanging.

Books that describe the history of Long Island portray the indigenous population as peaceful and compliant, willing to give their land and share their resources with the benevolent European settlers in exchange for the “enlightenment” delivered by the adoption of the superior European theology and culture. This is the peace the colonial historians love to tout when they write about Long Island Indians. They cite the various “treaties” to support their notion that the Indians were treated fairly and properly compensated for the loss of their territories.

From an indigenous perspective, “treaties” imposed by force are at best a one-sided peace and there can be no valid agreement for peace where the choices are cultural extinction, slavery or death. John Underhill, Lion Gardiner and the other puritan Easthamptoners framed Long Island history so that their conquest and cultural decimation appears in the best light. However, indigenous Long Islanders must not forget the thousands killed, the lives ruined in slavery, the generations displaced and forever changed. Nothing any historian writes will ever excuse that.